Part 2: Smoke and Mirrors—Vladimir Iorich, the Russian Oligarch Behind Cobalt 27

Digging up Russian roots

Series: Unpacking Canada's Cobalt 27, Nickel 28 & Blockmint Technologies

A. Introduction

It begins with a curious omission.

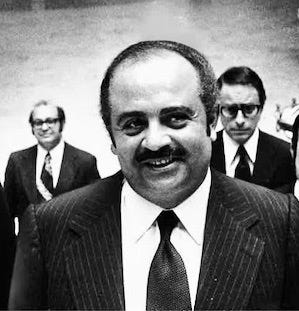

Cobalt 27 Capital Corp., a Canadian-listed battery metals company, didn’t disclose that one of its architects and co-founders was Vladimir Iorich, a figure far more familiar in Kremlin circles than Bay Street boardrooms.

Iorich, one of the oligarchs who emerged from post-Soviet privatization, remained absent from the company's public filings until after a crucial $200 million IPO. And even then, only as a passive investor with no control over Cobalt 27.

His absence raises a question: why would a public company hide the identity of one of its architects from investors it courted?

It’s a question that also haunts its sister company, Voyager Digital Ltd., which later collapsed amid allegations of operating a Ponzi scheme.

In Part 1, we identified Michael Beck as one of the original architects of Cobalt 27.

Now, in Part 2, we follow the trail of another: Russian oligarch Vladimir Iorich, and uncover other connections. His path stretches from the coal mines of Siberia to the commodities corridors of Zug, Switzerland, where American fugitive Marc Rich cast a long and consequential shadow.

B. Siberian Roots

To understand Vladimir Iorich, we start in Siberia.

Born in Novokuznetsk, a city shaped by industry in the coal heartland of the Russian Federation, Iorich graduated from the Kuzbass Polytechnic Institute in 1980, and began work at Gidrougol, the state coal agency. By 1988, he was deputy, then commercial director, of the Yubileynaya coal mine.1

Working in a Siberian coal mine is hardly a pathway to Russian oligarchy.

But Iorich’s ascent was shaped by two powerful figures: Boris Yeltsin, and Marc Rich.

C. Yeltsin: Privatization for Patronage

In 1992, President Boris Yeltsin, advised by a handful of Harvard and University of Chicago economists, launched one of the most radical economic experiments of the late 20th century: the transformation of the world’s largest planned economy into a capitalist one virtually overnight.

Grand promises were made: every Russian citizen would be issued a stake in the newly privatized economy; factories would flourish under private ownership; the economy would grow; prosperity would follow.

The promises weren’t kept.

Rigged auctions transferred ownership of valuable oil companies, mines, airliners, smelters, rail networks, and coalfields to Yeltsin insiders. State enterprises were purposely collateralized, defaulted on by design,2 and transferred to select beneficiaries for a fraction of their value.

Petr Aven, a banker and participant in the process, later admitted the obvious: under Yeltsin, the Russian economy became “highly criminalized.” The architecture of privatization was not capitalism; it was kleptocracy. Certain men were appointed millionaires—or billionaires—not by merit, but by allegiance to Yeltsin.3

Anatoly Chubais, Yeltsin’s Privatization Minister, later conceded that the oligarchs who seized Russia’s major assets then crippled its economy, demanding government credits and subsidies to sustain the very enterprises they had looted.4

As for ordinary Russians, privatization brought not prosperity, but poverty, alcoholism, and social collapse. One described the outcome brutally:

“A handful of thieving oligarchs feasted amid general starvation.”5

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Boris Berezovsky, and Roman Abramovich were among the most prominent beneficiaries of Yeltsin-era privatizations.

In between deals with fugitive commodities trader Marc Rich, Khodorkovsky established Bank Menatep, one of Russia’s first private financial institutions. In 1995, under the government's corrupt auction program, Anatoly Chubais assigned Menatep the task of administering the auction for control of Yukos Oil Company. In a transaction emblematic of the era, Khodorkovsky’s own bank selected him as the winning bidder. He acquired Yukos for $350 million, when it was estimated to be worth at least $6 billion.6

After Khodorkovsky took over, Yukos began selling crude oil internationally at $8.60 per barrel, $4 below market.

As one observer put it:

Khodorkovsky was “skimming over 30 cents per dollar of revenue, stiffing his workers on wages, and destroying the value of minority shareholders.”7

Khodorkovsky sold crude oil and other commodities from Russia at artificially low prices to himself itself via shell companies in Switzerland. These shell entities then resold the same commodities to international buyers at full market prices, diverting the revenues so that they never went back into the Russian economy.

The architect of the strategy to loot the state and offshore the proceeds for personal gain was not a Russian—it was Marc Rich.

Author Paul Klebnikov noted:

“Marc Rich had been “gouging the Russians, buying commodities at insider prices, selling them abroad, and registering his profits in Zug, Switzerland.”8

Boris Berezovsky, a car salesman, and Roman Abramovich, a mechanic, represent two additional oligarchs who gained control of Russian companies before privatization even began.

According to the law firm Skadden Arps, which represented Abramovich in Moscow for a lengthy period of time, Berezovsky leveraged his deep political connections to become Abramovich’s “roofer” (godfather)9, opening doors for Abramovich and helping him get Russian companies inexpensively. In exchange for this protection, Abramovich took money from Russian businesses, and funneled it for years to Berezovsky.10

Berezovsky eventually fled Russia when he was investigated for looting and money laundering.

The godfather protection money still flowed.

Over time, more than £1.73 billion was laundered to Berezovsky from Abramovich through an intricate network of offshore entities to obscure its origin.

In a particularly elaborate arrangement, later described by a UK court as a “money laundering scheme”, British attorney Stephen Curtis charged fees of £18 million to route £1.475 billion of Abramovich’s godfather payments through Sheikh Sultan bin Khalifa al-Nahyan in the United Arab Emirates, who charged 15% commission (£221 million) to move the proceeds to Berezovsky.11

The Yeltsin oligarchs, whether they remained inside Russia or abroad, found ways to keep being monetized.

D. The Marc Rich Playbook

Iorich’s second pillar was the fugitive commodities trader Marc Rich.

In 1974, he founded Marc Rich + Co. AG, the firm that would later evolve into Glencore International. In 2001, he was controversially pardoned by Bill Clinton.

Rich’s model was simple: trade where other could not, or would not, and extract profits through secrecy and leverage.12

In 1983, Rich was indicted in the United States on 65 criminal counts for fraud, racketeering, and violating U.S. sanctions, after trafficking oil from Iran during the U.S.-Iran hostage crisis. He fled to Zug, Switzerland, where, despite an Interpol red notice, he remained beyond prosecutors' reach for nearly two decades.13

Switzerland was his safe haven; that country made his operations possible, providing legal, political and institutional protection.

Friends in the Criminal Underworld

Rich specialized in moving oil to and from terrorist states and sanctioned markets,14 using intermediaries, commodity blending, and shell companies to obscure origin and destination.15

Rich’s operations extended far beyond conventional commodities trading. They intersected with organized crime and individuals with well-documented affiliations. According to the U.S. government, Rich propped up the Russian mafia, and developed deep ties with many of the mafia leaders.16

To operate in sanctioned markets and conflict zones, Rich required more than traders—he relied on smugglers, intermediaries, and men who could move money invisibly across borders.

In Angola and Sierra Leone, Rich traded oil with Marat Balagula,17 a gangster aligned with the Lucchese crime family, part of the American Cosa Nostra.

In Russia, he worked with Adnan Khashoggi, an arms trafficker and securities fraudster who was a key figure in Iran-Contra. Adnan Khashoggi was one of the founders of Canada’s Barrick Resources (later Barrick Gold).18 Michael Beck’s partner, Stephen Dattels, was one of its employees.

Rich and Khashoggi reportedly partnered to open an electronics store in Moscow.19 At the time, Khashoggi was raising funds alongside Berezovsky and Chechen mafia leader Khozh-Akhmed Nukhaev.20

Canadian Underworld

In Bulgaria, Rich’s partner was TIM, widely regarded as a front for the Bulgarian mafia.21 Its financier, Nikola Damyanov,22 a Canadian from Bulgaria, moved commodities through companies like Fertitron Inc., including during the Yugoslav wars and into regions under U.S. and U.N. embargo.

After the 2005 assassination of Bulgarian banker Emil Kyulev, a figure tied to TIM, authorities discovered that Damyanov and Ivan Todorov, one of Bulgaria’s most notorious mafia bosses, were on a hit list created by a rival mafia group.23

Rich’s Canadian ties didn’t end there.

He maintained ties to Boris Birshtein,24 a Canadian businessman, and head of Seabeco, a firm long suspected of laundering money for European organized crime.25

According to Ukrainian mob boss Semion Mogilevich, he and Birshtein were close friends.26 Seabeco did business with Laco AG, a Zug company co-owned by a Rich associate and Yevgeny Leibovitz, Balagula’s son-in-law.

One thread of this story surfaced unexpectedly in my inbox one morning from an anonymous tipster.

In my inbox were documents about Vladimir Petropoljac and his Russian wife, who had been charged with laundering criminal proceeds in Malta. They had arranged to move $70 million from Russia into Canada. The money was set to pass through the trust account of a Vancouver securities attorney. I looked into the attorney; he is married to an Iranian. The attorney was then set to move the money to a Vancouver company, controlled by another Iranian national. The Vancouver company CEO flew to Frankfurt to meet Petropoljac at the Hilton Airport Hotel. Hours before the meeting, Petropoljac abruptly cancelled. He was in Sicily, the stronghold of the Cosa Nostra, meeting with Glencore.

Rich’s network extended even further. It included Grigori Luchansky,27 founder of Nordex, an Austrian firm funded by Rich and investigated for nuclear weapons trafficking. Luchansky cultivated ties to Western political circles, including dinners with Bill Clinton.28

Despite an indictment for fraud, racketeering and illegal commodities trafficking with Iran, and longstanding dealings with gangsters and transnational organized crime, Marc Rich remained a magnet for business partners.

One of them was Vladimir Iorich.

E. Taking over the Kuzbass Coal Empire

Little is publicly recorded about Vladimir Iorich’s early business activities. What is known is that he emerged from the Yeltsin-era privatizations with control of major coal mines and plants in the Kuzbass.

The privatization of Russia’s coal industry unfolded more gradually than other sectors, owing to its strategic importance to the economy.29 The Kuznetsk Basin, known as the Kuzbass, is a vast coal formation in Siberia’s Kemerovo Oblast, home to an estimated 725 billion tons of coal.30 For decades, it powered Soviet industry.

In the mid-1990s, Iorich met Igor Zyuzin, then the commercial director of another Siberian coal mine. Together, they established Uglemet, a Russian company through which they began acquiring controlling interests in key Kuzbass operations.31

Over time, they built a network of companies that controled extraction, transportation, and sales. They incorporated Mechel OAO in Russia, and Conares Holding AG in Zug, Switzerland, Marc Rich’s adopted town.

Their decision to base operations in Zug was no coincidence because by that point, Rich, Iorich and Zyuzin were partners.

Forging the Russia - Swiss Axis

In 1992, Marc Rich had acquired the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant under privatization.

Rich’s business model aligned with what Petr Aven described as a “highly criminalized” economic environment.

Author Paul Klebniov again on Rich:

“He'd strike a deal with the local party boss, or directors of a state-owned company. He'd say, ‘OK, you will sell me the [commodity] at 5 to 10% of the world market price. I will deposit some of the profit I make by reselling it 10x higher on the world market, and put the kickback in a Swiss bank account.’”32

Whether bribes or kickbacks were paid, or which officials may have benefitted in the transfer of the Chelyabinsk plant to Rich, remains undocumented. What is clear is that Rich needed operators to manage the plant and export its metals. Iorich and Zyuzin stepped in under Mechel, running the facility and moving product to international markets.

Following Marc Rich’s model, they exported coal through Zug—“earning their first big money,” as one Russian reporter put it—and reinvested the proceeds into new acquisitions.33

Through this cycle, they acquired OAO Southern Kuzbass for $50 million.

In 2001, they bought the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant from Marc Rich for $133 million, consolidating control over a major steel operation.

Under Yeltsin’s watch, the spree of auctions and acquisitions continued.

Additional acquisitions included Mezhdurechenskugol, expanding their grip on Siberian coal production, and diversifying into ferroalloys and steel. In 2004, using a BVI shell called Little Echo Invest Corp., they won an auction to acquire a 25% blocking stake in Yakutugol, the largest coal mining enterprise in Yakutia.34 Iorich told Russian media the “victory” would open new regional opportunities for Mechel.35

Threads of Marc Rich remained embedded in Mechel. In a 2006 prospectus, OAO Southern Kuzbass disclosed that in 2003, Marc Rich’s Glencore advanced $25 million to Conares Trading AG in Zug. The loan was guaranteed by Southern Kuzbass. Meanwhile, in the BVI, Little Echo became Southern Kuzbass’ largest creditor—after Southern Kuzbass effectively bought the Yakutugol stake from itself, in what amounted to a circular deal.36

By the close of the Yeltsin era, Vladimir Iorich had transformed from commercial director of one Siberian coal mine into co-owner of one of Russia’s largest coal and steel conglomerates.

He and Zyuzin were now newly minted Russian oligarchs.37

Packaging for Wall Street

By the early 2000s, Vladimir Iorich and Igor Zyuzin controlled a vast network of coal, ferroalloy, and steel assets across Siberia.

The next phase was monetization, and for that, they turned to Western capital markets.

In 2003, they consolidated their holdings under a new corporate structure: Mechel Steel Group OAO, formalizing the assets accumulated during the privatization era.

In October 2004, Mechel listed 11% of its shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

The IPO raised $335 million and valued the company at just under $3 billion.

Among Mechel’s largest customers, according to its prospectus: Marc Rich.38

I noticed some things were kept out of the U.S. prospectus by the New York attorneys—like the fact that Iorich told Russian reporters that Mechel was selling metal to Marc Rich’s Glencore, which was reselling it to Iran:

“Мы продаём металл Glencore, который уходит в... Иран, с которым они умеют работать.” (“We sell metals to Glencore, which ends up in … Iran, with whom they know how to work”)39

“They” meant Marc Rich, whom Iorich was explaining, knew how to trade with Iran.

Before the IPO, Iorich and Zyuzin each controlled 42.97% of Mechel,40 through offshore vehicles, including Conares Holding AG in Zug, Switzerland.

The Slow Exit

At the beginning of 2006, Iorich announced plans to sell his shares41 and establish a new venture: Pala Investments in Zug, where he was moving.

Despite these announcements, public filings and media reports suggest that Iorich remained closely tied to Mechel, at least initially.

In March 2006, Coal magazine reported that he was in Kemerovo to sign a coal agreement with the governor.42 Russian media noted that his son, Yevgeny Iorich, had joined Mechel.

By the end of that year, Mechel’s shareholder disclosures confirmed that control remained concentrated among the original insiders and their proxies.

F. Government Scrutiny of Mechel

After Yeltsin’s resignation, a new generation of political leaders began to reassess the legacy of privatization, and oligarch-controlled conglomerates came under closer scrutiny.

Mechel was among them.

In 2008, President Vladimir Putin publicly criticized Zyuzin and Mechel during a televised meeting, because Mechel was selling coal to Russian firms at nearly double the price charged to foreign buyers. Following the broadcast, Versia reported:

“Rumors spread that, in reality, the margin is settled in offshore companies associated either with Zyuzin or with Iorich.”43

The implication, whether valid or not, was unmistakable—and it harkened back to the 1990s: to Rich, Berezovsky, Khodorkovsky, Abramovich.

G. The Canadian Front

As Mechel faced mounting scrutiny at home, its founders looked abroad again, this time to Canada’s junior mining sector.

In 2007, a small Canadian-listed mining company, Oriel Resources PLC, began seeking a buyer.

One of Oriel’s founders was Sergei Kurzin.

Like Iorich, he was born in Siberia.44

Like Iorich, he had worked for Marc Rich in Russia during the 1990s.45 He had also worked with Abramovich at a gold mine in Russia.

Kurzin and other insiders, along with members of the Rich family, had also made significant donations to Clinton-affiliated organizations.

Buying $100 million for $73 million

Many months before it put itself up for sale, Oriel completed a transaction unusual even by Canadian mining standards.

It acquired the Tikhvin Ferroalloy Plant in Russia from a group that included Alexander Nesis, Alexander Mamut, and Ehud Rieger, men who had all profited from Yeltsin’s privatization. The deal was rumored to be backed by Abramovich,46 the oligarch who was paying Berezovsky protection money through offshore fronts.

Tikhvin was no prize. It was under construction and entangled in litigation. Oriel nevertheless paid $241 million, issuing shares at a premium.

The second half of the transaction was stranger.

The vendors also sold Oriel $100 million in cash held in a British Virgin Islands bank account. In real terms, Oriel paid $73 million for the $100 million—but the shares were again issued at a premium, creating the illusion that the price paid matched the offshore money.

It didn’t—strip away the artificial premium, and the implied fee for moving $100 million from Russia to Canada via the Caribbean was 27%.

And it gets stranger.

The shell company holding the $100 million—Croweley International Limited— was directed by someone named Linda Blimpied. According to Kazakhstan government records, Blimpied also directed the holding company that sold Oriel the rights to a Kazakh mine—the same asset it was now reselling to Croweley et al.

Whomever she was fronting for, Linda Blimpied had a foot in both camps.

The Mechel Oriel Deal

By 2008, when Oriel went looking for a buyer, its economic picture was bleak. Its assets consisted of two mining licenses in Kazakhstan, and Tikhvin—still incomplete.

Oriel had no production and posted a net loss of $5.3 million in 2006.47 By the end of 2007, losses had ballooned to $38 million. In the span of four months, the company had raised $316 million through a reverse takeover, a debt facility, and a private placement. Within a year, it had spent most of it, more than $250 million—an aggressive cash burn for a pre-revenue mining company. At least $49 million of that spend was not tied to any identifiable project asset.48

On March 3, 2008, the Russian business daily Vedomosti reported that Mechel was considering a takeover of Oriel. The tip had come from the Canadian side.49

Following the leak, Oriel’s share price jumped 10.6% in one day. Two days later, it climbed another 7.8%.

Experts in Russia warned that Oriel’s valuation was inflated. One analyst at IG Kapital estimated its true worth at between $500 and $550 million. Another put it at closer to $400 million.50

Nevertheless, Mechel agreed to acquire Oriel at a 13.7% premium, valuing the company at $1.498 billion (£749 million), or $2.19 (£1.10) per share.51

For context: Iorich and Zyuzin had purchased Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant, one of Russia’s largest fully operating steel producers for $133 million.

If a fully functional giant like Chelyabinsk was worth $133 million, how could Oriel, with an unfinished small ferroalloy plant, and two mining licences, justify a $1.498 billion valuation?

It was another deal that defied commercial logic.

Inflated Valuations Deflate

Five years later, the inevitable reckoning came.

In 2013, Mechel sold the Tikhvin Ferroalloy Plant, and Oriel’s Kazakh mining rights to a Turkish buyer for $425 million. The Russian analysts who warned of Oriel’s inflated valuation had been right all along.

During Oriel’s early financing rounds, insiders had acquired shares at £0.01 each. When Mechel agreed to pay a premium £1.10 per share, those insiders secured a 10,900% return—a 109x gain.

The Oriel deal delivered a spectacular exit for its founders. For Mechel, it was a financial disaster. The company lost $1.073 billion on the transaction, wiping out 71.6% of the value it had paid if it wrote down all of the deal.

Around the same time, a nearly identical scenario unfolded in Paris.

In 2007, the French nuclear giant Areva SA acquired Uramin Inc., another speculative Canadian mining company, for $2.5 billion. Uramin was linked to some of the same individuals behind Oriel. Years after the acquisition, Areva discovered the uranium licences it had bought were essentially worthless because the deposits were unviable.

Areva ultimately wrote off almost the entire $2.5 billion.52 Investigations in multiple jurisdictions followed.53

In both deals—Mechel-Oriel and Areva-Uramin—Canadian junior mining companies were sold at extreme valuations to foreign countries, and written off. And in both, the same names appeared:

Stephen Dattels

Michael Beck

Sam Jonah

SRK Consulting.

H. Forward Agreements Redux

Extreme valuations were only part of the story. Another was the use of forward agreements.

After Mechel closed its acquisition of Oriel, it emerged that Oriel had gone to Marc Rich’s Glencore and secured a forward agreement.54 It provided that if and when Oriel began producing from its Kazakh mine at Voskhad, Glencore would purchase 60% of the output.

At the time, Voskhod was not a producing mine, and the agreement was never disclosed in Oriel’s public filings.

Just as some of the individuals behind Oriel resurfaced at Uramin Inc., they resurfaced too at Cobalt 27 – and again at Voyager Digital Ltd., the defunct crypto exchange.

And at Voyager, a forward agreement surfaced.

Before Voyager even launched its crypto trading platform, it signed a forward agreement with Jump Trading, a major high-frequency trading firm.55

The agreement was concealed from investors during Voyager’s public listing process.

Voyager’s January 2019 filing spoke only of “plans to develop relationships with liquidity providers”56—with no mention that it had already committed future customer crypto assets to a trading desk.

No disclosure came until October 2019, when Voyager issued a belated news release acknowledging the deal.

By then, retail investors had already entrusted the platform with their assets—unaware that Voyager’s earliest commitment wasn’t to them at all—it was to a high-frequency trading firm.

Smoke and mirrors from the very beginning.

Coming Next: Part 3 —Cobalt-for-Stock Deals

In the next part of our "Smoke and Mirrors" investigation, we examine Cobalt 27’s cobalt-for-stock barter scheme and how tens of millions of dollars’ worth of raw cobalt were exchanged with an unfathomable grouping of counterparties, including an absurd deal to buy raw cobalt from an 80-year-old doctor in Oregon who tends the flowers at a gated senior community.

“Vladimir Iorich”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Iorikh.

“Comrades-in-Arms”, Vanity Fair, November 13, 2012, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/politics/2012/11/roman-abramovich-boris-berezovsky-feud-russia.

OAO Alfa Bank v. Center for Public Integrity, No. 1:00-cv-02208-JDB (September 27, 2005), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCOURTS-dcd-1_00-cv-02208/pdf/USCOURTS-dcd-1_00-cv-02208-0.pdf.

Stephen White, “The Russian Oligarchs, from Yeltsin to Putin”, European Review 23, no. 4 (October 2015).

OAO Alfa Bank, supra note 3.

“Yukos Kingpin on Trial”, CorpWatch, July 19, 2004, https://www.corpwatch.org/article/yukos-kingpin-trial.

Bernard Black et al., “Russian Privatization and Corporate Governance: What Went Wrong?”, Stanford Law Review 52, no. 6 (2000), https://doi.org/10.2307/1229501.

Paul Klebnikov, Godfather of the Kremlin: Boris Berezovsky and the Looting of Russia (New York: Harcourt, 2000).

A roofer is a person, or group, usually an organized crime group, which provides protection pursuant to a criminal extortion racket carried out with threats of violence or exposure, in exchange for under-the-table payments.

Berezovsky v. Abramovich [2012] EWHC 2463 (Comm); Berezovsky v. Abramovich [2008] EWHC 1138 (Comm).

Berezovsky, supra note 10.

Daniel Ammann, The King of Oil: The Secret Lives of Marc Rich (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009).

The only other person I am aware of who evaded the US Marshals for decades with foreign country and deep institutional protection like Marc Rich, is Francisco Franco, who allegedly escaped from a US prison in 1987, and has been wanted ever since. He moved to the Dominican Republic, where he lives a very visible and public life. One of his daughters became the right hand man to the country’s president. His other daughter married the top narcotics trafficker, Caesar Peralta.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Government Reform, Justice Undone: Clemency Decisions in the Clinton White House, 107th Cong., 2nd sess., H. Rept. 107-454, vol. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2002), https://www.congress.gov/107/crpt/hrpt454/CRPT-107hrpt454-vol1.pdf.

Jessica Reaves, “The Marc Rich Case: A Primer,” Time, February 13, 2001, https://time.com/archive/6931694/the-marc-rich-case-a-primer/.

U.S. House of Representatives, Justice Undone, supra note 14.

Ian Smillie, Blood on the Stone: Greed, Corruption and War in the Global Diamond Trade (London: Anthem Press, 2010).

“Saudi Arabian Billionaire Adnan Khashoggi’s Visit to Canada,” YouTube, 1984.

Mark Colodny, “Khashoggi to Team Up with Marc Rich?,” Fortune, August 13, 1990, https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1990/08/13/73891/index.htm.

“Chechnya Cannot Ignore Russia Yet,” The Economist 342, no. 8002 (February 1, 1997).

“Ascent of Bulgarian TIM,” Capital, December 10, 2007, http://www.capital.bg/weekly/03-02/11-2.htm.

U.S. Embassy Sofia, “Bulgaria’s Crackdown on Organized Crime: Is it Real or is it Memorex?,” Cable No. 05SOFIA1882_a, November 2, 2005, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/05SOFIA1882_a.html.

“Bulgarian Mafia Bosses Trial Turns Farcical,” Novinite, December 9, 2009, https://www.novinite.com/articles/110888/Bulgaria+Mafia+Bosses+Trial+Turns+Farcical.

Анатолий Беня, «Владимир Следнев: Кучма, мафия и я.», Украина криминальная, June 3, 2003, https://cripo.com.ua/investigations/p-1430/.

“Solnzewo-Bruderschaft,” Wikipedia, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solnzewo-Bruderschaft.

Tom Burgis, Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the World (New York: Harper, 2020).

Владимир Иванидзе, «Интервью с Шабтаем Калмановичем,» Коммерсантъ, no. 54 (April 17, 1997).

U.S. House of Representatives, Justice Undone, supra note 14.

Igor Artemiev and Michael Haney, The Privatization of the Russian Coal Industry: Policies and Processes in the Transformation of a Major Industry (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002).

“Кузнецкий угольный бассейн,” Википедия, https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Кузнецкий_угольный_бассейн.

“Интервью: Владимир Иорих, совладелец и гендиректор Стальной группы ‘Мечел,’” Ведомости, March 21, 2005.

“How Marc Rich Helped Plunder Russia,” New York Post, February 15, 2001, https://nypost.com/2001/02/15/how-marc-helped-plunder-russia/.

“Игорь Зюзин богатеет, погружая ‘Мечел’ в долги,” Versia.ru, July 31, 2023, https://versia.ru/igor-zyuzin-bogateet-pogruzhaya-mechel-v-dolgi.

"Мечел купил блокпакет 'Якутугля'," Rusmet, January 24, 2005, https://rusmet.ru/press-center/mechel_kupil_blokpaket_yakutuglya/.

“Мечел» запасся «Якутуглем»,” Kommersant, January 24, 2005, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/541568.

ОАО «Южный Кузбасс», Проспект ценных бумаг, утверждён November 22, 2006.

Sergei Guriev and Andrei Rachinsky, “The Role of Oligarchs in Russian Capitalism,” Journal of Economic Perspectives19, no. 1 (Winter 2005), https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330053147994.

Mechel Steel Group OAO, Final Prospectus (Washington, DC: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, October 29, 2004), https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1302362/000119312504181382/d424b4.htm.

Ведомости, March 21, 2005, supra note 31.

Versia.ru, July 31, 2023, supra note 33.

Rumafia.net, “Иорих Владимир Филиппович,” https://rumafia.net/ru/dosje/402?hl=BSP.

Ugol, OOO “Redaktsiya zhurnala Ugol” 2006.

Versia.ru, July 31, 2023, supra note 33.

Peter Schweizer, Clinton Cash (New York: Harper, 2016).

“A Russian’s Underground Route to the Stock Market,” The Telegraph, February 15, 2004.

Rebecca Bream, “Abramovich Behind Move for Oriel Resources,” Financial Times, September 15, 2006.

Ирина Малкова, «Акционеры Oriel сдались "Мечелу"», Ведомости, April 17 2008, https://www.vedomosti.ru/library/articles/2008/04/17/akcionery-oriel-sdalis-mechelu.

Oriel Resources PLC. 2007 Annual Financial Report. (London: Oriel Resources PLC, 2008).

Temkin, Anatoly, and Yulia Fedorinova. “Ориел сплавляется с «Мечелом».” Ведомости, March 3, 2008. https://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2008/03/03/oriel-splavlyaetsya-s-mechelom

Дмитрий Смирнов и Евгений Хвостик, «"Мечел" дорого заплатит за ферросплавы», Коммерсантъ, № 36 (3853), March 5, 2008, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/863665.

Ведомости, April 17, 2008, supra note 47; Mechel OAO. Recommended Cash Offer for Oriel Resources PLC. (Moscow: Mechel OAO, March 26, 2008).

Martine Orange, “The Riddle of How French Nuclear Giant Areva Blew €2 Billion in Mining Meltdown,” Mediapart, January 18, 2012, https://www.mediapart.fr/en/journal/france/180112/riddle-how-french-nuclear-giant-areva-blew-2-bln-euros-mining-meltdown.

“Uramin: le scandale qui plombe Lauvergeon,” L'Express, February 17, 2014, https://www.lexpress.fr/societe/justice/uramin-areva-et-lauvergeon_1762669.html.

Елена Бутырина, «Oriel Resources Plc Қазақстанда жалпы құны 800 миллион доллардан асатын хром және никель жобаларын жүзеге асыруда», Панорама, July 21, 2008.

Investigation Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of Voyager Digital, LLC, filed October 7, 2022, United States Bankruptcy Court, Southern District of New York.

Filing Statement of UC Resources Ltd., January 16, 2019.